As promised a while ago, today’s post goes into more detail about the removal of mould from books.

At the beginning of this year, I helped Ian Beaumont (freelance leather conservator) for a day and a half to clean the books in two bookcases in the Library at Kedleston Hall. Fortunately, the mould outbreak was spotted early on, which meant that most books just needed a little precautionary dusting. In a future post, I hope to talk a bit more about the dos and don’ts of book cleaning in general.

First things first: it is impossible to get rid of mould. Spores will always remain in the air and will always settle on surfaces if the conditions are right. Therefore, in an ideal world, one would create an environment which inactivates mould spores. Unfortunately, this is not always possible when books are kept in historic environments.

Once mould is detected, it is advisable to treat it as if the spores were still active – it is regarded a biohazard which could affect people’s health. Preferably wear disposable vinyl gloves and use a dust mask “conforming to EN149 category FFP2S” (National Trust Manual of Housekeeping, p. 84).

If the outbreak is not serious, it is possible to use a home-made extraction hood and a vacuum cleaner, fitted out with a HEPA (“High Efficiency Particulate Air”) filter. Above is a device I used at Calke Abbey recently. Note that the nozzle of the vacuum cleaner is covered with muslin, which is to stop any loose fragments from bindings being sucked up and to protect fragile surfaces.

Depending on the fragility of the binding, either a pony hair brush or a bristle shaving brush is used to clean the mould off the book in the direction of the vacuum nozzle.

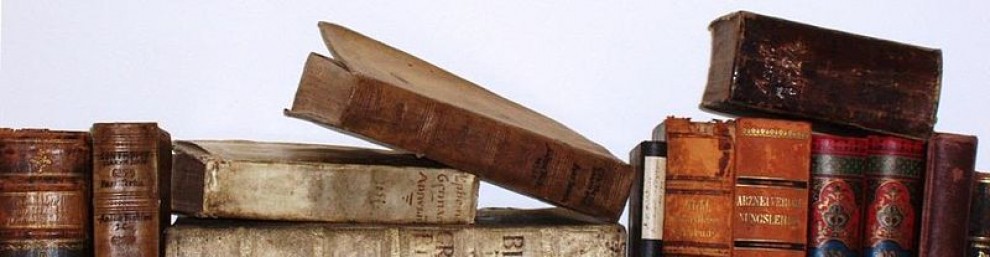

So, back to Kedleston. Here, the books in one of the cases were (of course!) rather larger than the octavos I cleaned at Calke. The first step was to take them off the shelves and stack them systematically, without disturbing the order of the books. Secondly, the empty shelves were wiped clean with a duster.

Then, Ian set about cleaning the books. Before I get any comments: yes, I know he’s not wearing gloves in these images! However, the book he’s cleaning only needed a dusting, and he most definitely wore them while cleaning the mouldy books…

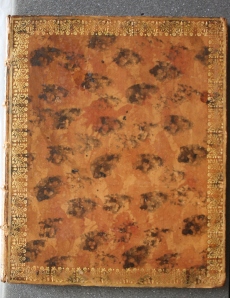

The actual removal of mould is therefore not rocket science, but needs to be approached with some care and awareness of one’s own health. Moreover, in the case of these eighteenth-century books, specialist knowledge of how to handle and clean them safely (i.e. without damaging them!) was also required.

Therefore, unless you know what you’re doing, when a serious mould outbreak is detected, get in touch with a professional book conservator for specialist advice, for example via ICON’s conservation register.

Sources:

- R.E. Child, Mould (London: Preservation Advisory Centre, 2004, revised 2011) [http://www.bl.uk/blpac/pdf/mould.pdf]

- The National Trust, Manual of Housekeeping (London: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2006), chapters 8 (Biological agents of deterioration) and 42 (Books)

With thanks to Ian for allowing himself to be photographed 🙂

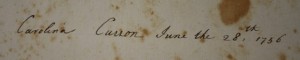

This little volume can be found on the shelves in the Library at

This little volume can be found on the shelves in the Library at