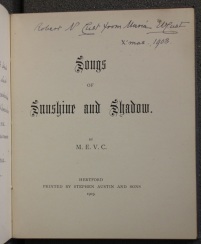

“Read with much fun in 1911, LMY”. Whether this was meant as a sincere expression – or not – of her appreciation of the “indifferent verse” written by Maria Eleanor Vere Cust, her husband’s cousin-once-removed, Louisa Yorke clearly left one of her trademark comments after reading the volume. “Indifferent verse” is how Maria Cust’s biographer describes the poetry presented in Lucem sequor and other poems (1906), and to judge from an earlier privately printed publication, Songs of sunshine and shadow (1903), the comment is fairly apt. Both works at Erddig are inscribed to Maria’s father, the orientalist Robert Needham Cust, for whom she worked as a secretary. Although the name “Cust” appears infrequently in the Erddig book collections outside the Library, it highlights the continuing connections between the two families. Continue reading

“Read with much fun in 1911, LMY”. Whether this was meant as a sincere expression – or not – of her appreciation of the “indifferent verse” written by Maria Eleanor Vere Cust, her husband’s cousin-once-removed, Louisa Yorke clearly left one of her trademark comments after reading the volume. “Indifferent verse” is how Maria Cust’s biographer describes the poetry presented in Lucem sequor and other poems (1906), and to judge from an earlier privately printed publication, Songs of sunshine and shadow (1903), the comment is fairly apt. Both works at Erddig are inscribed to Maria’s father, the orientalist Robert Needham Cust, for whom she worked as a secretary. Although the name “Cust” appears infrequently in the Erddig book collections outside the Library, it highlights the continuing connections between the two families. Continue reading

Category Archives: Female authors

Mills & Boon at Calke Abbey

Apologies for recycling last post’s image!

As I mentioned the last time, I had not come across a Mills & Boon to catalogue before, although if it were ever to be found in a historic library, it would have to be in Calke Abbey’s weird and wonderful collection of about 10,000[!] volumes.

Gerald Mills (1877-1928) and Charles Boon (1877-1943) met at Methuen, and set up their own publishing house in 1908. Although Mills & Boon is associated today with romantic fiction of a formulaic nature, the firm initially established itself as publishers of high-quality fiction and non-fiction. Mills had a background in education and focused on signing authors who could write text-books to be used in schools (and so ensure a wide distribution). Until the start of World War I, Mills and Boon were hugely successful in this field.

Joan Sutherland’s romantic fiction set in India may be an indication of the reversal of fortune for the firm in the 1920s. Because of its size, it was unable to compete in the field of literary fiction with larger power houses, such as Methuen and Macmillan, and in fact, Desborough also seems to have been published by Hodder and Stoughton. From the mid-1920s onwards, the firm focused more and more on romantic, escapist, fiction for women, issuing between two and four new titles every fortnight in the 1930s.

- Joseph McAleer, ‘Mills, Gerald Rusgrove (1877–1928)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/73895, accessed 3 Jan 2014]

- Joseph McAleer, ‘Boon, Charles (1877–1943)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/73896, accessed 3 Jan 2014]

Chronological collections (2)

In an earlier post, I talked about a small quarto volume in the Library at Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire. This book, an abbreviation of John Jackson’s Chronological antiquities, I believe was written by Mary Assheton, Lady Curzon (1695-1776). Mother of Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Baron Scarsdale (who built the existing mansion), she has never received much attention beyond the fact that she created a rococo garden on the edge of Kedleston estate. However, Mary is gradually emerging as an intriguing character in her own right (Here she is posing as a shepherdess in an Arcadian landscape); I will get back to her in a future post in more detail.

Today, I want to reflect a bit more on the contents of the Chronological collections itself. It is one of those slightly ironic twists of historical research that the copy of Jackson’s Chronological antiquities which was at Kedleston in 1765, was sold at auction in June 1888, as part of a ‘tidying up’ exercise of the book collection. Neither do we have a record of the purchase of the book. Without further research (or more serendipity!), it is therefore impossible to know whether Mary or her husband, Nathaniel Curzon, 4th Baronet (died 1758), purchased the Kedleston copy of the Chronological antiquities, and whether Mary annotated it in preparation for her abbreviation.

What is so fascinating about her project, if we can assume the comment in the Leicester University copy of Chronological collections is correct, is that she wrote it ‘for the use of her sons’. Both Nathaniel and Assheton, his younger brother, were adults in 1755, and Nathaniel had been married for five years. So, Mary could not have written it for their personal education. However, both men (not untypically for their time) were keen to present themselves as well-educated connoisseurs of art, good taste, and fashions, in order to advance themselves in society. Since so much of eighteenth-century British culture relied on a knowledge of ancient history (Greek, Roman, Egyptian, and Hebrew), but also showed an interest in the exotic (that is, the Far East), Mary’s abbreviation can be read as a quick reference guide to the main civilisations of the past. We are beginning to see that she was a driving force behind the social aspirations of her sons, and that she took an active interest in her son Nathaniel’s building activities at Kedleston from late 1758 onwards.

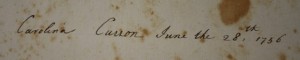

Although there were two copies of her abbreviation in the Kedleston Library in the nineteenth century, when the National Trust took over ownership in the mid-1980s, only Caroline Curzon’s copy remained. It is possible that the second of the two copies was similarly the victim of the late nineteenth-century auction sales.

This little volume can be found on the shelves in the Library at

This little volume can be found on the shelves in the Library at